Introduction

Evals are what turn a voice demo into something people can rely on. The gap between “seems fine” and “works every day” is almost always evals.

This guide shows how to evaluate voice systems by slowly building complexity: start simple (Crawl), add realism (Walk), then test multi-turn (Run). Along the way, you’ll learn to build the three things that make results robust: a dataset, graders, and an eval harness, plus a production flywheel so real failures become new tests.

Teams that invest in evals can ship to production 5–10× faster because they can see what’s failing, pinpoint why, and fix it with confidence.

Part I: Foundations

1) Why realtime evals are hard

Realtime is harder than text because you are grading a streaming interaction with two outputs: what the assistant does and how it sounds. A response can be “right” and still sound broken.

1.1 The 2 axes of realtime quality

Text evals mostly ask if the content is right. Realtime adds a second axis: audio quality. Content and audio can fail independently, so a single score can hide real problems.

Most realtime evals can reduce to two independent axes:

-

Content quality: Did the assistant understand the user and do the right thing? Correctness, helpfulness, tool choice, tool arguments, and instruction following.

-

Audio quality: Did the assistant sound acceptable? Naturalness, prosody, pronunciation, stability, and how it behaves under noise and imperfect capture.

1.2 Hard to debug

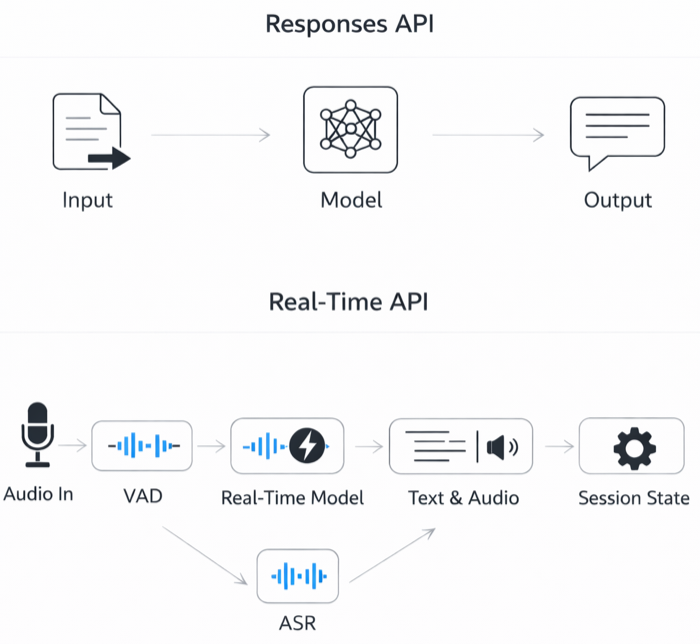

With the Responses API, the mental model is simple: request in → response out. With the Realtime API, a “turn” is a stitched pipeline. That orchestration makes voice apps easy to build, but for evals, you must log stages so you can isolate failures and find root causes.

A “turn” is a chain of events (speech start/stop → commit → response.create → audio deltas → done), and failures can happen at any stage. If you treat the system as a black box, you’ll chase “model issues” that are actually turn detection, buffering, or tool-integration issues.

Example:

-

Content is correct but the experience is broken: audio gets chopped during barge-in because the interruption boundary is wrong.

-

Answer is “right” but feels slow: latency came from network quality, turn detection slowness, not the model’s reasoning.

You can learn more about the various events that the Realtime API triggers here.

1.3 Transcript ≠ ground truth

In realtime api, the ground truth for “what the user said” is the actual audio signal (what the microphone captured and what the model heard). A transcript is not ground truth, it’s a model-produced interpretation of that audio. It can be wrong because it’s constrained by transcription model errors.

If you treat transcripts as truth, your evals can be misleading:

-

False fail: ASR drops a digit, but the model heard it and called the tool correctly → your LLM grader marks “wrong.”

-

False pass: transcript looks clean, but audio was clipped and the model guessed → you miss the real problem.

Best Practices:

-

Improve transcription: Iterate on transcription prompts, try different models, try different methods such as oob transcription.

-

Use transcripts for scale: run most automated grading on transcripts + traces.

-

Calibrate graders on messy reality: iterate graders on production-like, noisy transcripts (not clean text) so they don’t overreact to ASR errors.

-

Add an audio audit loop: spot-check ~1–5% of sessions end-to-end.

Part II: Strategy

2) Crawl / Walk / Run

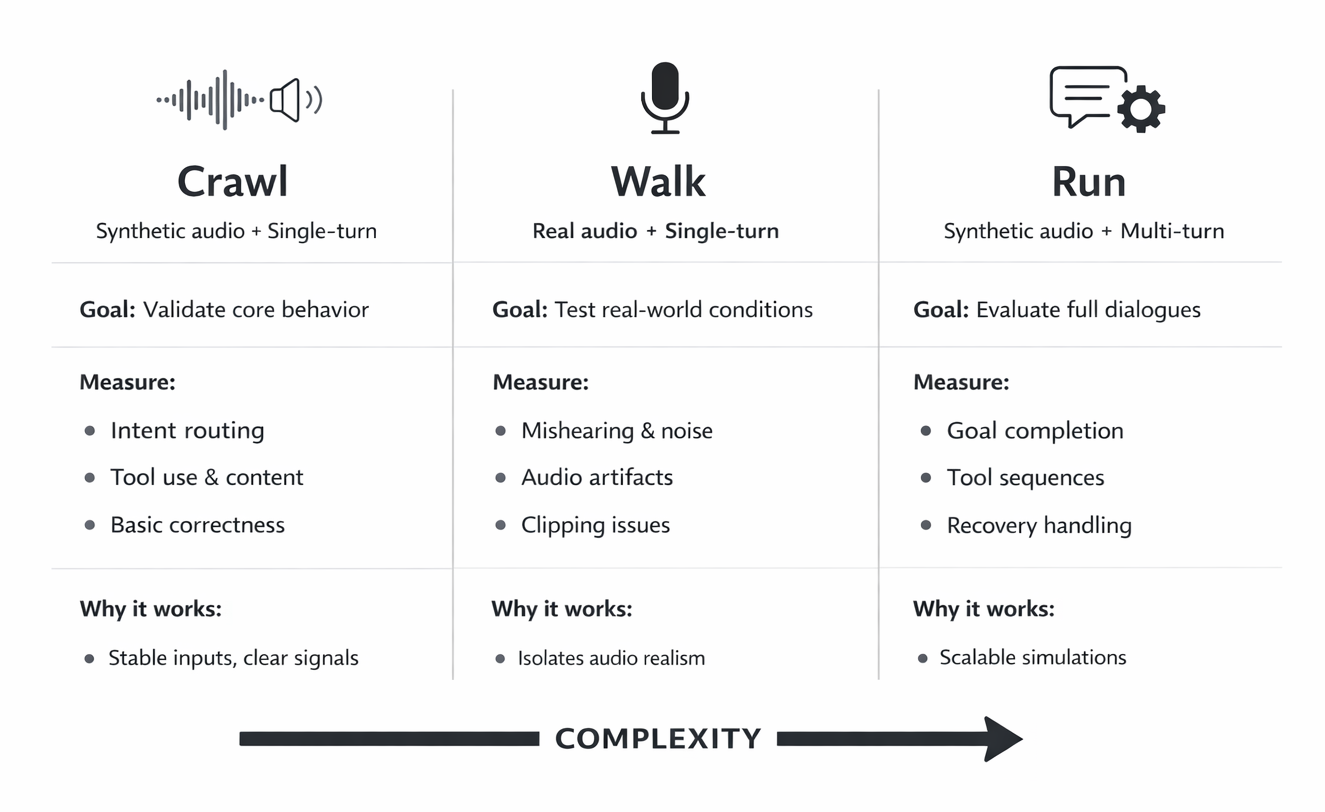

Realtime evals feel overwhelming when teams start at the hardest setting: real audio, multi-turn dialogue and real tools. The fix is to build complexity in steps. If your system cannot crawl, it will not run. Early evals should be simple enough that failures are diagnosable, repeatable, and cheap to iterate on. You can increase complexity in two independent axes.

2.1 Isolating input conditions: clean vs production audio

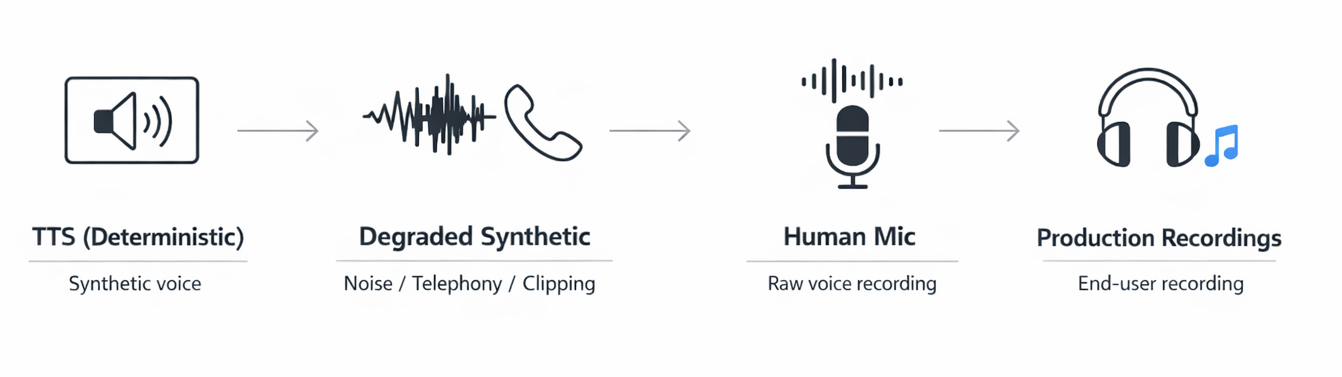

This axis is about what the model hears. By controlling input audio conditions, you can separate failures in model intelligence from failures in speech perception.

-

Start with synthetic audio → tests intelligence:

- Use clean, synthetic repeatable audio (e.g., TTS) when you want to measure the model’s reasoning and decision-making without audio variance muddying the signal → helps isolate intent routing, tool calling, instruction following

-

Move to noisy, production-like audio → tests audio perception:

- Once intelligence is stable, introduce audio that resembles production: compression, echo, far-field capture, background noise, hesitations/self-corrections. This tests whether the system still behaves correctly when the input is ambiguous, messy, or partially lost → helps measure mishearing words, robustness to acoustic variations

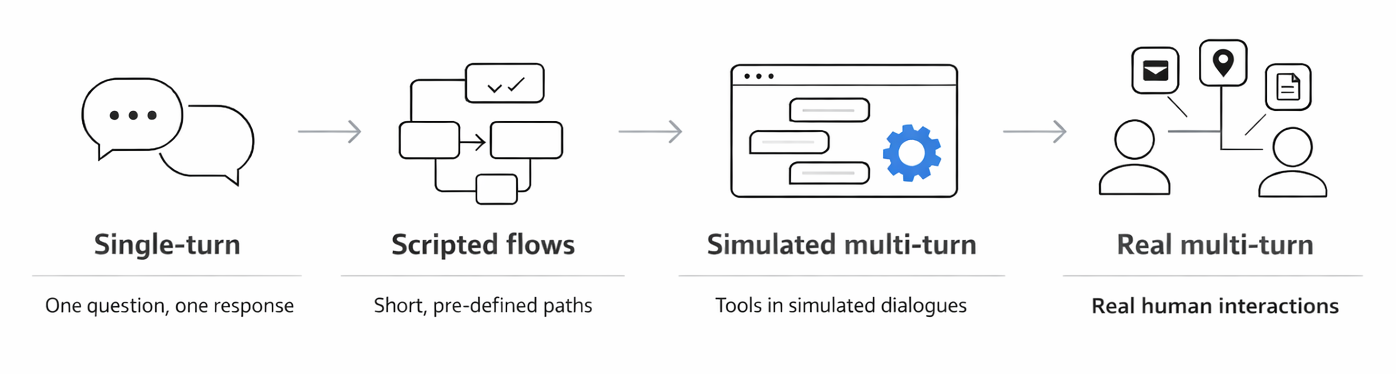

2.2 Isolating interaction conditions: single-turn vs multi-turn

This axis is about what you are evaluating: are you evaluating the next turn or the full conversation.

-

Start single-turn → tests core competence:

- Run one request → one response when you want the cleanest signal on fundamentals: correct intent routing, correct tool choice, valid arguments, and basic instruction following. If the system can’t reliably pick the right tool or produce a valid schema here, evaluating more turns won’t help.

-

Move to multi-turn → tests robustness:

- Once single-turn is stable, move to multi-turn where the system must hold goals and constraints across turns, sequence tools correctly, recover from tool failures and handle user corrections. Multi-turn shifts you from turn-level correctness to episode-level outcomes: did it complete the goal, how many turns did it take, and did it recover cleanly when something went wrong?

Single-turn tells you can win the battle; multi-turn tells you can win the war.

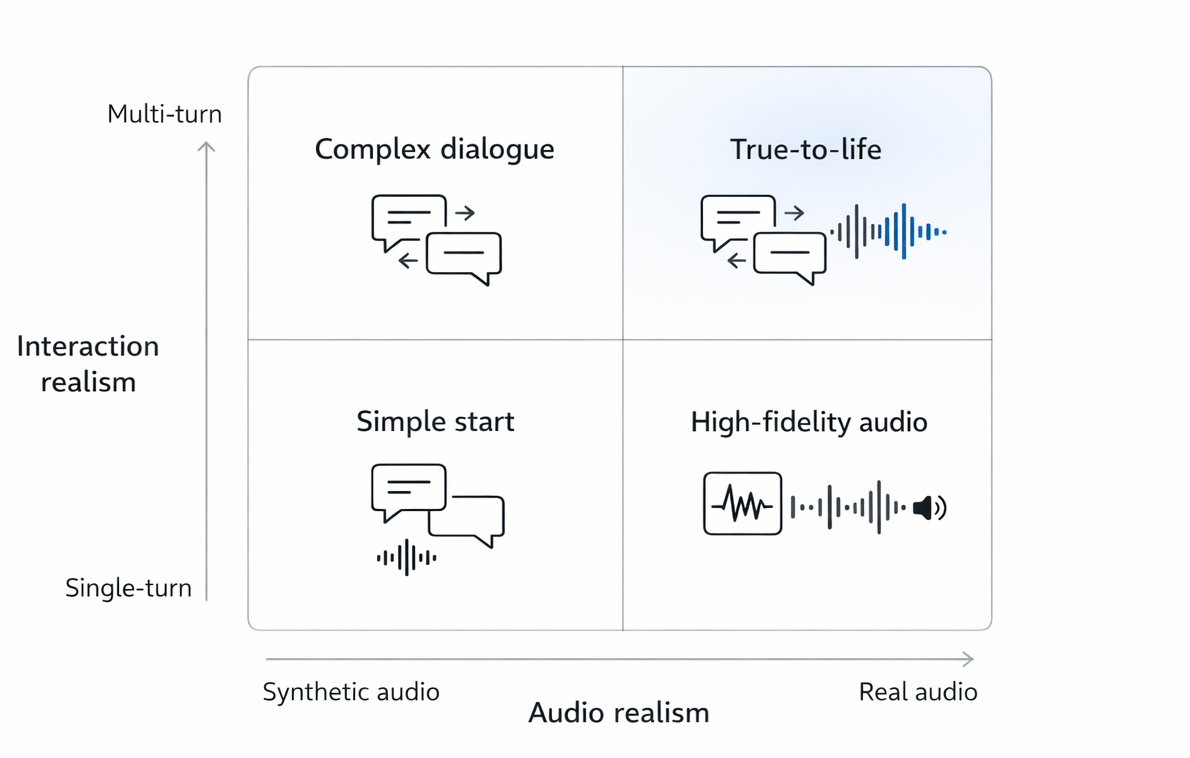

2.3 Eval Quadrants

Use a 2x2 map for evaluation: right = more realistic audio, up = more realistic interaction. Start bottom-left, increasing difficulty one axis at a time.

Eval modes (increasing complexity):

-

Crawl (bottom-left): synthetic audio + single-turn

-

Walk (move right): real noisy audio + single-turn

-

Run (move up): synthetic audio + multi-turn simulation

Top-right (real audio + full multi-turn flow) is manual eval: run end-to-end sessions the way users do in production. Keep it in the loop for the entire project lifecycle.

Example:

User: “Change my reservation to 7pm.”

- Crawl: You feed deterministic TTS for “Change my reservation to 7pm,” then grade only the next assistant turn: it should route to the reservation-update tool and pass the correct time=7pm (or ask one tight clarifying question if a required identifier is missing).

- Walk: Record a human-mic version of “Change my reservation to 7pm,” then replay the same utterance with phone-bandwidth compression and light background noise; the system should still hear “7pm” (not “7” or “7:15”) and produce the same correct tool call.

- Run: Model simulating a user outputs “Change my reservation to 7pm,” then simulates realistic follow-ups (“It’s under Minhajul for tonight… actually make it 7:30… wait, tomorrow”) plus an injected tool error once; the agent should clarify only what’s missing, keep state consistent, recover cleanly, and end with a single correct update tool call reflecting the final expected outcome.

You can find reference implementations that you can start from and adapt here realtime eval start.

Part III: The three building blocks

4) Data: building a benchmark

4.1 Start with a “gold” seed set (10–50)

Cover the flows you cannot afford to fail: core intents, must-work tool calls, escalation and refusal behaviors. Generate quickly, then have humans review for realism and gaps.

The goal is to start, not to perfect.

4.2 Build for iteration, not just volume

Eval datasets exist to drive iteration, not to look big. The loop is the product: run evals → localize failures to a specific behavior → change one thing → re-run → confirm the fix improved without regressions. A benchmark is “good” if it makes that loop fast, repeatable, and easy to diagnose.

That requires coverage, not raw count: you need to represent the actual user behaviors and the specific edge cases that cause production failures. Size alone won’t surface fragility; the right coverage will.

Coverage also has to be balanced. For every behavior, include both positives (the system should do X) and negatives (the system should not do X). Without negatives, you reward shortcuts.

Customer Example: A team built a voice support bot and optimized hard for the “escalate_to_human” tool call. Their offline score hit 98 percent on escalation. In dogfooding, the bot started escalating for almost everything. The root cause was dataset imbalance. They had many “must escalate” cases and almost no “do not escalate” cases, so the model learned a shortcut: escalate whenever uncertain.

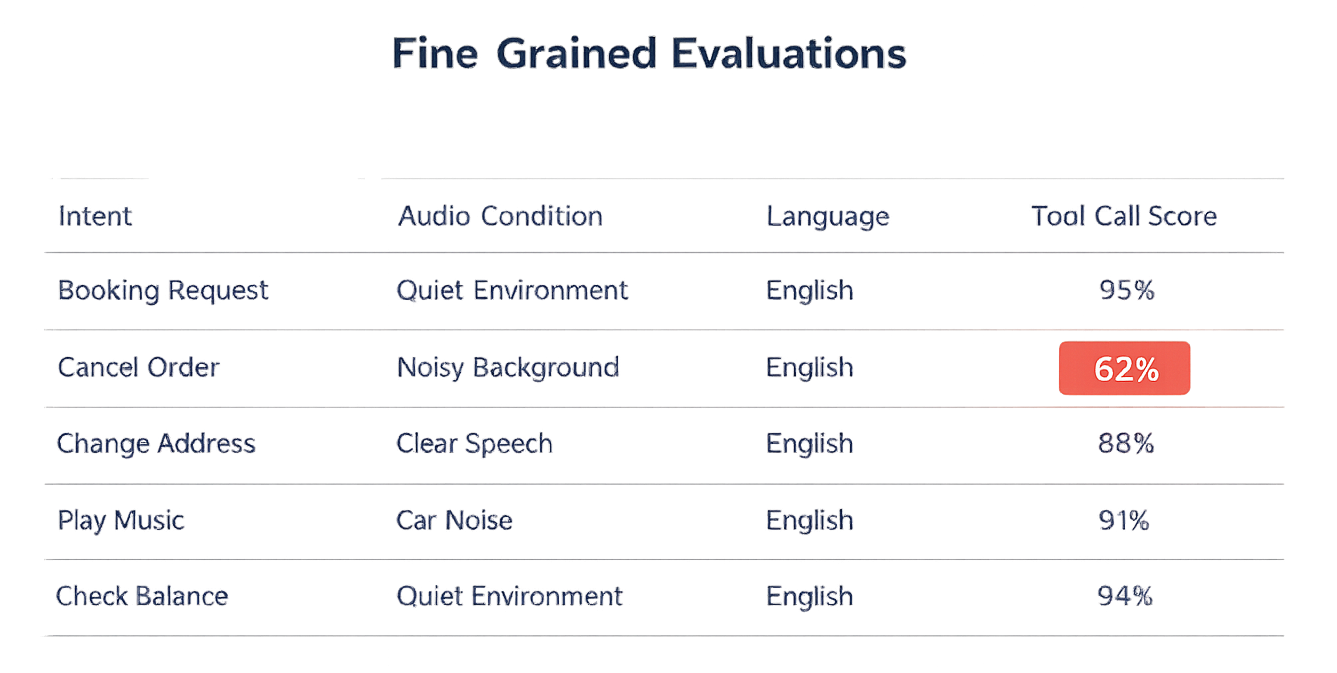

Finally, you must precisely tag your data to enable fine-grain evaluations. These tags should provide the necessary detail to move from a general observation, like "score dropped," to a specific root cause, such as "this intent fails under these audio conditions with this policy boundary."

Example of tags could be:

- intent, expected outcome, audio condition, language, and expected tool call. Tagged data enables teams to run fine-grain evaluations leading to faster iteration loops.

4.3 Expand from production failures

Offline evals are how you iterate fast. They are also easy to outgrow. If you keep optimizing against a fixed benchmark, scores can rise while real quality (reality) stalls because users do things your dataset does not cover.

The operating model is a loop: production expands the benchmark. A new failure shows up, you reproduce it, you label it, and you add it. Over time, your offline suite should grow with the product.

A simple way to manage this is three sets:

-

Regression suite: hard cases you already fixed. Run on every prompt, model, and tool change. This is your “do not break” contract.

-

Rolling discovery set: fresh failures from production and near misses. This is where you learn what you are missing and what to prioritize next. If they trigger failure modes, promote them to your offline dataset. Teams usually fill this by:

-

Running online graders to catch failures directly, and/or

-

Watching proxy metrics (latency, tool error rates, escalation rate, retries) and sampling data when they drift.

-

-

Holdout set: a subset of the offline test which stays untouched that you run occasionally to detect benchmark overfitting. If test scores climb while holdout stays flat, you are training for the test.

5) Graders

Graders are your measurement instruments. They turn a messy, real-time voice session into signals you can trust.

5.1 Manual review (highest leverage)

Manual review = listen to real audio + read full traces end-to-end. It’s the fastest way to build product intuition and catch the failures users notice instantly. Automated evals tell you what you can measure. Manual review tells you what you should be measuring.

What automation routinely underweights (but users feel immediately):

-

Turn-taking failures: awkward gaps, double-talk, model cutting the user off.

-

Pacing & prosody: model speech is too fast/slow, rambling, flat, jittery, “robot polite.”

-

Transcript mismatch: ASR lag/drops/normalization → you end up grading the wrong thing.

-

Eval-system bugs: missing coverage in the golden set, mislabeled expectations, graders that are systematically too strict/lenient.

Customer Example: one large company had execs spend ~3 hours/day just listening to sessions and scanning traces. They surfaced “hidden” issues, early cutoffs, phantom interruptions, awkward prosody, that would’ve sailed past offline evals.

5.2 Automated graders

Humans don’t scale. Without automation, regressions slip through and “improvements” turn into vibes.

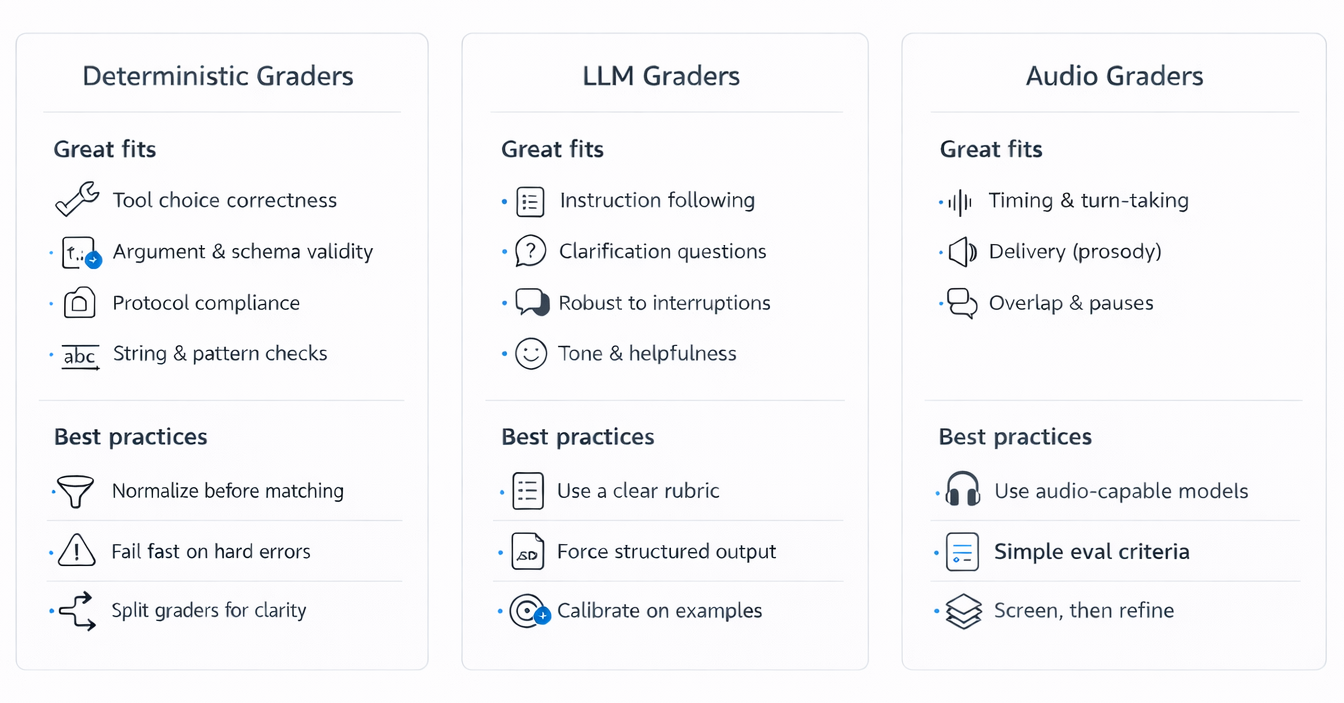

Use a layered grader stack:

-

Deterministic graders for anything objective and machine-checkable. They’re fast, cheap, and stable, perfect for tight iteration loops and regression gates (tool calling, JSON validity, string and pattern checks).

-

LLM graders help you measure the things that matter but don’t fit neatly into deterministic rules: correctness, instruction following, whether a clarification was appropriate, completeness, and helpfulness.

-

Audio graders because users experience the voice, not the transcript. Audio is still the hardest to judge reliably, so don’t wait for a single perfect scorer, start with simple, measurable checks (silence, overlap, interruption handling) and layer richer rubrics over time.

6) Eval Harness

A realtime eval is only as trustworthy as the harness that runs it. A good harness has one job: make runs comparable. If the same input can’t be replayed under the same settings and produce similar outcomes, it makes it hard to measure and iterate.

6.1 Start with single-turn replay (the “Crawl” harness)

Start here. Single-turn replay gives the fastest, cleanest signal because you can keep almost everything fixed. Keep the exact audio bytes, preprocessing, VAD configuration, codec, and chunking strategy identical across runs.

In practice, it’s often best to start with voice activity detection (VAD) turned off so you remove one major source of variance. With VAD off, you decide exactly when a user turn ends.

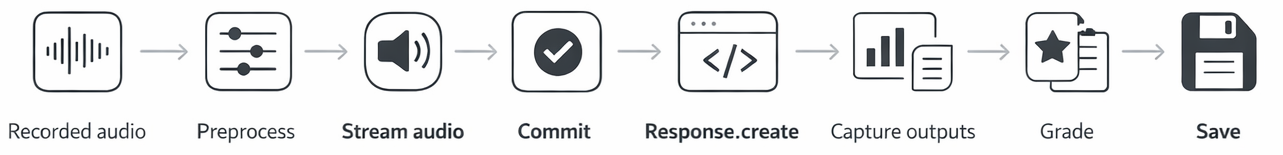

A simple single-turn harness looks like:

More explicitly (in Realtime API terms):

-

Generate or load input audio

-

If the datapoint is text, generate TTS audio.

- Often, starting with text → TTS → audio is the best first step because it enables much faster iteration. It’s easier to tweak and refine the eval when you can iterate on text quickly.

-

-

Stream audio into the input buffer

-

Send audio in fixed-size chunks (for example: consistent frame size per chunk).

-

Important: chunking and timing affect behavior. Pick a standard and stick to it. For example, 20 ms per chunk is a good balance of responsiveness and overhead.

-

-

Commit the user audio

-

(Recommended) With VAD off: commit immediately after the last audio chunk.

-

With VAD on: the server detects turns boundaries.

-

-

Trigger the assistant response

-

With VAD off: Call response.create to start generation.

-

With VAD on: It is automatic.

-

-

Collect outputs

-

Output audio chunks (streaming deltas)

-

Output transcript (if enabled)

-

Tool calls / tool arguments (if any)

-

Final completion event

-

-

Grade and persist

-

Run graders

-

Save results

-

6.2 Replaying saved audio (the “Walk” harness)

When you move from synthetic TTS to real recordings, the harness changes in one important way: you are streaming audio buffers from saved realistic audio.

For saved audio, the flow becomes:

How to make the evals realistic in practice:

-

Preprocessing must match production

-

Same resampling, normalization, channel handling, noise suppression (if used), and encoding.

-

Store preprocessing config alongside results so you can explain score changes.

-

-

Streaming policy must be explicit

-

If you care about latency: send chunks on a fixed cadence (e.g., “every 20ms, send 20ms of audio”).

-

If you only care about iteration speed: you can stream faster, but keep chunk size constant.

-

-

Turn boundaries must be repeatable

-

Prefer VAD off + manual commit for offline reproducibility.

-

If you must use VAD on (to match production), log VAD settings and track boundary events so you can debug failures.

-

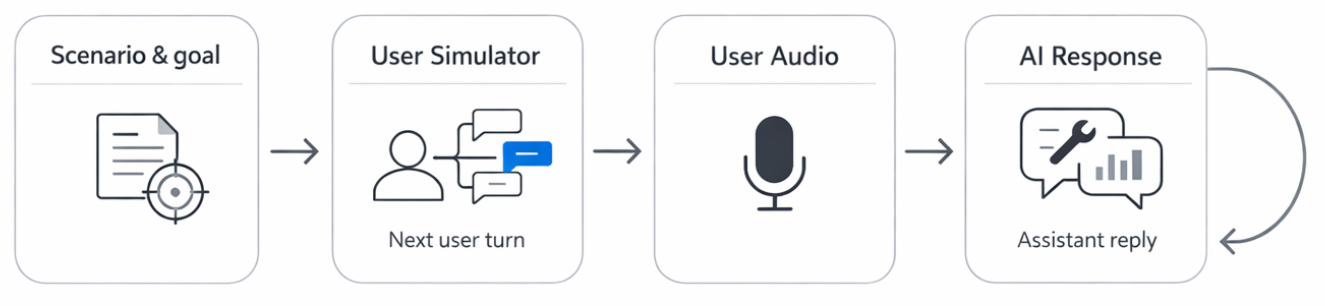

6.3 Model-simulated multi-turn (the “Run” harness)

Model-simulated multi-turn uses a user simulator to generate the next user turn for a full conversation. It can increase coverage of scenarios, but only if episodes stay comparable across runs.

Common loop:

Best practice for simulations:

-

Pin and version the simulator prompt: Treat it like code. A small prompt edit can shift behavior more than a model change.

-

Constrain randomness: Fix temperature and sampling settings. Use a seed if available. Use deterministic turns where it makes sense (i.e User greetings).

-

Mock tools deterministically: Define expected tool output mocks for the scenario and return those exact outputs when the assistant calls tools. This keeps the environment stable and makes runs comparable.

-

Record the full trajectory: Store every generated user text turn plus the final audio bytes you streamed. Persist tool calls, tool returns, and timestamps. Simulation is a discovery engine. When it finds a real failure mode, you backfill it into a deterministic scripted episode for the crawl or walk method.

Part IV: Case study

7.1 Customer support voice bot

Product goal and constraints

Resolve common support requests through tools, quickly and safely. The bot must collect the right details, call the right backend actions, and comply with policy. It must escalate cleanly when it cannot help. It must handle frustrated callers without becoming verbose or brittle.

Crawl, Walk, Run plan

Crawl: synthetic + single-turn

Focus on routing and policy. Given a short request, the bot should pick the right intent, request missing info, and avoid unsafe actions. Use deterministic synthetic audio so you can rapidly iterate on tool schemas and prompts.

Walk: real + single-turn

Test understanding under realistic capture. Use synthetic or real recordings in noisy environments and telephony-like quality. This is where order numbers, names, and addresses break on noisy audio. Evaluate whether the bot asks clarifying questions instead of guessing.

Run: synthetic + multi-turn simulations

Simulate full workflows with simulated users with gpt-realtime and tool mocks: authentication, account lookup, order status, return eligibility, refund, ticket creation, escalation. Add adversarial but realistic patterns: caller changes goal midstream, provides partial info, talks over the assistant, or answers a different question than asked.

Manual Review:

Run internal call sessions against staging systems. This catches UX failures that graders miss: overlong disclaimers, repetitive questions, poor turn-taking during authentication.

Core dataset buckets and useful slices

-

Top intents: order status, return, refund, cancel, billing issue, password reset, appointment scheduling.

-

Missing and conflicting info: wrong order number, two accounts, caller provides a nickname, caller refuses to authenticate.

-

Policy edges: out-of-window returns, restricted items, partial refunds, subscription cancellation rules.

-

Escalation triggers: the bot should hand off when confidence is low or tools fail.

-

Emotional tone: angry, rushed, confused. The content goal stays the same, but delivery matters.

Graders used

-

Deterministic: tool selection, tool argument validity, policy phrases if required.

-

LLM rubric grader: instruction following, resolution correctness, empathetic tone, whether it avoided hallucinating policy, whether it escalated appropriately, and whether it stayed concise.

-

Audio grader: long silences, interruption handling.